Developed by chemists from Stanford, the new battery swaps out lithium from the cell in favor of aluminum. In the past, aluminum batteries have failed fast, managing just 100 recharge cycles before they start to degrade.

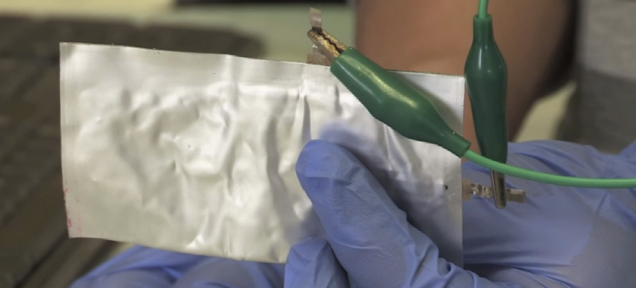

The new cell uses aluminum for its anode—the negatively charged electrode in the battery—and graphite for the positive cathode. The resulting cells can undergo 7,500 recharge cycles without losing capacity—far better than old aluminum cells, and in fact better than li-on batteries that usually begin to suffer after 1,000 cycles, and all that at a fraction of the price.

The battery can also charge incredibly quickly, reaching full capacity within a minute. Compared to li-on batteries they’re also rather more robust and won’t catch fire, even if drilled through - said Stanford chemistry professor Dai Hongjie, who created the cell.

There are, however, some downsides. First, the cells can only muster 2 volts across their electrodes—just over 50 percent of the voltage that li-on batteries can provide. Nor do they pack energy into themselves as efficiently, managing to store just 40 watts of electricity per kilogram, compared to 200 or so for li-on batteries.

Neither of those are deal breakers, says Dai:

...but improving the cathode material could eventually increase the voltage and energy density. Otherwise, our battery has everything else you'd dream that a battery should have: inexpensive electrodes, good safety, high-speed charging, flexibility and long cycle life. I see this as a new battery in its early days. It's quite exciting.Speedy charging may in fact be more desirable than absolute energy capacity for a given size. But for now, it’s at least interesting to know that a lackluster battery technology may yet prove incredibly useful.

0 comments:

Post a Comment